For almost 30 years, jewellery artist Liv Blåvarp has been creating organic and voluminous constructions out of wood. Since her American debut in 1995, international recognition of her work has steadily increased – most recently through her being awarded the Bayerische Staatspreis for 2012, at the international contemporary craft competition SCHMUCK (‘Internationale Handwerksmesse München’).

‘It’s largely about developing sculptural form’, explains Liv Blåvarp, when asked by NorwegianCrafts.no about her artistic intentions.

‘But you could also say the recurring theme in my artistic practice is to create structures that seem alive.’’

What does wood signify in this context?

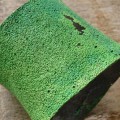

‘The most significant aspect is that it allows me to work with larger volumes without them becoming too heavy. At the same time, wood is that material which best allows me to create the expression I want.’ Liv Blåvarp: Red Drop, 2011. For this piece Blåvarp was awarded Bayerischer Staatspreis 2012.

Blåvarp’s jewellery is characterized by large, spectacular forms that naturally and elegantly follow the contours of the neck or wrist. They consist of many small elements combined into a flexible whole. For some works, she uses light wood types stained in lively colours. In others, she uses dark wood treated only with oil. In yet others, she mixes stained and dark wood types.

Tactility

Liv Blåvarp relates that wearability is a key factor in her art. The jewellery should function with the body, and she always tries things out on herself and others during the creation process.

s it about formal ideas?

‘Yes, a theme may emerge along the way, or a personality or story. But the most important thing for me is that the works should have a sensuous appeal. They should give a physical experience. When touching them, your emotions should become involved.’

Are there any artists you especially admire?

‘Dorothea Prühl and Bettina Speckner are two artists I respect highly. Here in Norway, Tone Vigeland. I cannot stress too strongly how important it is to have Norwegian artists who have presented strong exhibitions, received lots of attention and, not least, have been able to live on what they earn from their art.’

Choosing wood as a material

When Blåvarp attended the Norwegian College of Art, Crafts and Design (this has now become Oslo National Academy of the Arts, Department of Visual Arts), her first choice was not to work with metal. She wanted to study graphic design, but the relevant department did not accept her application. With no background in metal, she was compelled to find her starting-point outside the traditional framework. This resulted in a lot of experimentation.

‘For me, formal qualities eventually became the most important, and my greatest experience of mastery was to be able to build large three-dimensional forms. At the same time, I tested out different methods and approaches, both practical and creative.’

After finishing her degree in Oslo, Blåvarp went to London and studied for a year at the Royal College of Art. It was there she seriously began working with wood. Although growing up in a family of carpenters and living alongside her grandfather’s workshop, it was not until her diploma project that she began experimenting with wood. But then only as a detail: she created laminated veneer objects that framed compositions made of metal. In London, she pursued this lamination technique and allowed wood to be the dominant material in her jewellery.

The artists’ group Trikk

In 1984 Blåvarp returned to Norway and began collaborating with Trikk (which means ‘tram’), an artists’ group she helped start with six of her former fellow students. They set up a joint workshop, produced joint exhibitions and enriched each other with insights from their divergent backgrounds. The other members were Morten Kleppan, Millie Behrens, Lei Stangebye Nielsen, Kyrre Andersen and Tove Bekken.

We received attention from art historians, journalists and the public, and felt we were at the forefront of our own era.’

European jewellery art broke new ground in the 1970s and ‘80s. This was especially the case in the Netherlands but also in England. Artists started using completely new materials such as aerospace metals, plastics and textiles. The new jewellery was extremely colourful and triggered immense interest. When Trikk started up, these new currents were about to gain a foothold in Norway.

‘We felt we were pioneers. The attention was intense and we had many discussions and consultations in the workshop. We were playful and experimental. It was a ground-breaking period for us all. The unorthodox use of materials I saw amongst other European jewellery artists suited me, and it inspired me to continue working with wood.’

Blåvarp’s works from this period consist mainly of neck pieces and bracelets made with the lamination technique she developed at the Royal College of Art. They contain small pieces of differently-coloured wood types combined to create a checkerboard texture. The forms are simple and streamlined, and the basic circular shapes are divided in two and held in place with elastic drawstrings.

Spiral form

After three years with Trikk, Blåvarp returned to Gjøvik, the area of Norway where she had grown up. She was planning her first solo exhibition for the following year (1988) and wanted to move on artistically.

‘I was trying to crack a very hard nut. I wanted to move away from the laminated works and especially the large collars, which I felt were too stiff. They were simply uncomfortable to wear.’

Through trial and error, she eventually arrived at a completely new way to construct her jewellery. By combining small pieces of wood, she solved the problem of lacking flexibility, and because these elements had a wedged profile, they merged into a beautiful, vibrant spiral form.

Many of the works in her first solo exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet (‘the Artists’ Association’) were based on this spiral construction. It was so successful; she continued constructing spiral forms for the next ten years. At Kunstnerforbundet, however, she also presented a neck piece consisting of two banana-like forms – for which she received much attention. In addition there were smaller jewellery items, among other things, broaches and bracelets.

Birds

In 1991 Blåvarp held her next solo show, this time at RAM Gallery. It was a large exhibition consisting of 12 necklaces. Here she continued using the spiral construction but it no longer extended all the way around the neck; it was now supplemented with forms associated with birds.

‘By this time I had acquired a much larger artistic vocabulary and a greater maturity in planning the process and solving problems. I was also more technically competent.’

Where did you gain your technical expertise? Has someone taught you, or have you acquired this proficiency simply through your practice?

‘Like many artists, I’ve invented the techniques myself, step by step, through the various projects.’

Do you use advanced machinery?

‘No, the production involves no high technology. It’s a combination of working with machines and handicraft, but mostly the latter.’

What is your most important skill?

‘Patience. This is at the core of many skills; to endure and not to give up or lose sight of my goal. The time needed to achieve a good result is very long in this field.’

At the 1991 exhibition, one could see clear evidence of her patient assimilation of skills and judgment. The compositions were looser and more flexible than ever before. She now combined different forms in the same jewellery piece. Some elements were hollow, such that they could be seen through. The clasps were placed and composed in ways that added more playfulness to the overall expression.

‘Creating clasps is difficult. They must stand out but still be integrated in the whole composition. Sometimes I really struggle to achieve this; other times it just seems to click. These clasp forms are almost a theme in themselves.’

USA

Four years later, in 1995, Liv Blåvarp received a telephone call from the American dealer Charon Kransen, a specialist in promoting contemporary jewellery art. He wanted to present Blåvarp to the American public. She accepted his offer with thanks – it was her ticket to a large audience passionate about contemporary arts and crafts.

‘Entering the American contemporary craft scene has been very important for me, both financially and in terms of my reputation. I’ve always been concerned about the business side of things but have tried not to let it control my artistic choices. When I chose to establish myself in the USA, I knew my style would fit in, and that I mustn’t compromise my artistic expression.’

The collaboration with Kransen entails that she sends him works which he sells, either from the showroom in his New York flat, or at the contemporary craft and design fair SOFA (Sculpture Objects and Functional Art). In 2001, Kransen organized a large exhibition of Blåvarp’s works, and it travelled to several galleries in the USA. After this her career really started rolling.

‘He’s built a market for my art, which means I’m able to work fulltime in my workshop and still support my family.’

Form within form

Parallel to the American travelling exhibition, Liv Blåvarp continued developing artistically, yet without giving up the principle of creating structures that seem alive. She began developing jewellery consisting of two forms, an inner and an outer, which unite into a unified whole.

‘It was like a form within a form. I first developed two separate forms, then integrated them into one form. I coloured them differently to distinguish them from each other.’

With her American career running at full speed, Blåvarp had her hands full trying to satisfy the growing demand. Nevertheless, she still managed to produce works for a Norwegian exhibition. In 1996 she held her second show at Kunstnerforbundet. It had many points of continuity with the RAM exhibition but lacked the spiral forms. The aviary theme she abandoned while retaining zoological ideas. Many of these new works were inspired by animal bodies.

Five years later she held a large retrospective exhibition at Sørlandets Kunstmuseum in Kristiansand. This was a representative overview of her artistic practice from 1984 to 2001. It also included several new works. The most notable innovation could be seen in a jewellery series with concave forms. Up to 2001, all her works had been convex. The exhibition was accompanied by the book Liv Blåvarp: Jewelry 1984-2001, with texts by Marjorie Simon and Gunnar Sørensen.

Nature’s voices

For the exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet in 2005, Blåvarp went one step further. Many of the jewellery pieces here were furnished with nozzles, spouts or trumpet-like elements made of whale teeth.

‘These cavities, or openings, if you will, were meant to draw associations to breathing, to inhaling and exhaling, and ultimately also to sound, as if from a wind instrument.’

Was this a radical step for you?

‘In many ways, yes, but for me, it was a natural development from the concave forms in my retrospective exhibition. But perhaps the public thought it radical, or even provocative.’

Are these the most dangerous of your creations?

‘Perhaps they are the darkest or the most mysterious.’

One works is entitled ‘Spirits Talking’. Could you say something more about it?

‘The title is meant to say something about voices emanating from the deep, either from within oneself or from nature.’

Are they mythical voices?

‘Yes, maybe, but for me, the work has nothing to do with Norse mythology. It could suggest a general spiritual feeling which might arise by being surrounded by nature, more like what one finds amongst native peoples of North America. A strong feeling for nature can be found in all my works in one sense or another, but perhaps not as strongly as in this series.

Calculated streamlined form

At her most recent exhibition at Kunstnerforbundet in 2011, Blåvarp presented a jewellery series with a tighter visual idiom. The compositions were more calculated and, for the first time, produced in relation to precise drawings.

‘I wanted to test the results of thinking out forms in advance. And without doubt my forms have become tighter.’

One work from this exhibition was selected for the juried exhibition ‘Schmuck 2012’, and it was probably a factor contributing to her being awarded the Bayerischer Staatspreis.

‘This was a welcome encouragement. I’ve not received all that much attention in Europe and have for a long time thought I fit better in the USA. But maybe I’ve been mistaken.’

Could this be the start of a European career?

‘Well, it wouldn’t be done with the wave of a hand, but in the long term, perhaps it’s possible to achieve something. We shall see.’